| 日本即将发射金星探测器 (中国空间探测进展有点慢) |

| 送交者: 2010年03月16日11:04:07 于 [世界军事论坛] 发送悄悄话 |

|

|

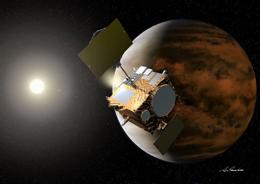

Japan prepares for Venus countdownAkatsuki probe could help to explain why Venus is so different from Earth.  Akatsuki will be Japan's first probe to Venus.A. Ikeshita / Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) Akatsuki will be Japan's first probe to Venus.A. Ikeshita / Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA)This week, Japan is shipping its Venus Climate Orbiter to the southwestern island of Tanegashima, where the satellite's launch is scheduled for 18 May. Project directors at the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) say they hope that the orbiter, Akatsuki (dawn), will resolve mysteries including how the atmosphere of Earth's scorching hot neighbour is able to 'super rotate' at speeds of up to 60 times that of its host planet. After a decade of neglect, scientists are returning their attention to the question of why a planet with so much in common with Earth is so inhospitable. The two planets are of a similar size and density, and are thought to have a similar iron core and rocky mantle. In addition, evidence from the European Space Agency's Venus Express, which has been orbiting the planet since April 2006, suggests that Venus might once have had water oceans. But unlike Earth, Venus is enveloped in sulphuric acid clouds and its surface temperature hovers at around 460 °C, thanks to a heat-trapping atmosphere of 95% carbon dioxide. It also lacks a strong magnetic field, which would protect nascent life from solar winds. In a spinHowever, the main target of the Akatsuki mission, which is scheduled to reach Venus in December, will be to solve the riddle of the super-rotation of Venus's atmosphere, which spins at 400 kilometres per hour. Venus itself rotates at a mere 6.5 kilometers per hour. Scientists have tried to understand the mechanism behind this phenomenon using data from the Venus Express, and various proposals have been put forward, but the answer remains inconclusive1,2.

"Most of these mechanisms could also be true of Earth, and then you'd have to explain why there is no super-rotation on Earth," says Takeshi Imamura, a member of the Planet-C project team at JAXA that is overseeing the mission. "It's very possible all of them are wrong. That's what we want to find out." Akatsuki will measure characteristics of different layers of the atmosphere at infrared, ultraviolet, infrared and radio frequencies. "In a simple way, one can view Akatsuki as a weather satellite for Venus, even if it can do a bit more," says Håkan Svedhem, project scientist for the Venus Express probe who is based at the European Space Research and Technology Centre in Noordwijk, the Netherlands. It is Akatsuki's orbit that will make it special, says Svedhem. In contrast to the polar orbit of Venus Express, Akatsuki will trace an elliptical orbit around the equator. This will allow the satellite to track the same part of the super-rotating atmosphere for up to 20 hours. "By tracking cloud features at different wavelengths it is possible to build a very good database of how the weather patterns and the super-rotation behave, at different depths, over this time," says Svedhem. Sail awayWith a camera dedicated to the purpose, Akatsuki could also become the first spacecraft to photograph lightning on Venus. So far, the strikes have been evidenced only by measurements from a magnetometer aboard Venus Express. ADVERTISEMENT <!--//--><![CDATA[//><!-- document.write('<script type="text/javascript" src="http://ad.doubleclick.net/adj/news@nature.com/;abr=!webtv;artid=article-one;pos=left;sz=300x250;ptile=2;ord=' + ord + '?" ></script>'); if ((!document.images && navigator.userAgent.indexOf('Mozilla/2.') >= 0) || (navigator.userAgent.indexOf("WebTV") >= 0)) { document.write('<a href="http://ad.doubleclick.net/jump/news@nature.com/;sz=300x250;ord=' + ord + '?">'); document.write('<img src="http://ad.doubleclick.net/ad/news@nature.com/;sz=300x250;ord=' + ord + '?" width="300" height="250" border="0"></a>'); } //--><!]]>

On the planet's surface, which is pock-marked with volcanic structures, both missions are looking for evidence of current volcanic activity. Akatsuki's broad-scope infrared camera can map much wider swathes of the surface in one go than can the equipment aboard the Venus Express. Any signs of volcanic activity could then be verified by Venus Express, which has powerful spectrometers capable analysing the chemistry in the identified regions. JAXA is hoping that the mission will also help to auger in a technical revolution. IKAROS, a 14-square-metre polyimide 'sail' will be launched at the same time as Akatsuki. An initial spin will spread the sail, which will then continue to rotate as it is propelled by the constant bombardment of photons from the Sun. The mass of photons hitting the sail at any one time will be just 0.1 grams. If all goes well, JAXA hopes to use a hybrid system consisting of a similar sail 50–100 metres wide and an ion-propulsion engine powered by solar cells to sail to Jupiter later this decade. |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

| 实用资讯 | |